Sharing First-Hand Accounts of Military Service

Sharing First-Hand Accounts of Military Service

(Family Features) More than a century after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles ended World War I, stories told by American veterans who served during this pivotal time offer fascinating insights into this period.

To preserve and share history as it happened through the lens of those who lived it, the Library of Congress Veterans History Project (VHP) collects these stories, and the stories of veterans who followed.

The individual stories of many of the veterans involved have been lost to time; however, the program encourages military veterans to document their experiences via first-hand oral histories, photos or written accounts. The stories are then made accessible so current and future generations may better understand what veterans experienced during their service.

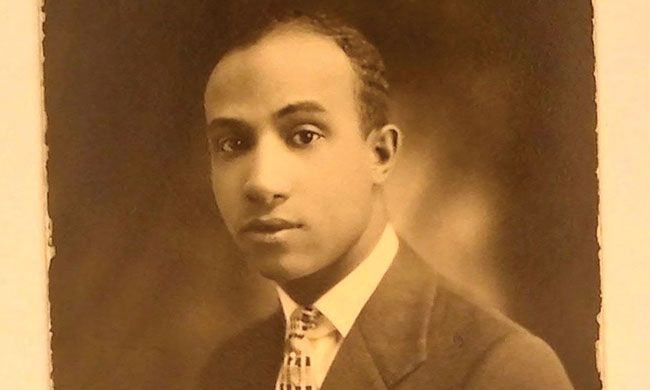

As time passes, new submissions from veterans who served in World War I have become increasingly rare, but occasionally, something special is uncovered, such as two submissions from Sherie Lockett: collections from her grandfathers, both African American World War I veterans.

As time passes, new submissions from veterans who served in World War I have become increasingly rare, but occasionally, something special is uncovered, such as two submissions from Sherie Lockett: collections from her grandfathers, both African American World War I veterans.

Containing 34 original letters, Jessie Calvin Lockett’s collection provides a unique insight into his experience serving in France as a stevedore, loading and unloading cargo ships.

The collection of Sherie Lockett’s grandfather, Arthur Singleton, includes a unique find: a 105-year-old diary.

When Singleton joined the Army in 1918, he was assigned to the 803rd Pioneer Infantry Brigade, a segregated unit tasked with constructing and repairing infrastructure.

Singleton’s diary is notably VHP’s first written account from a Black soldier who served during World War I. Entries detail his time in service, from training at Camp Grant to enduring harsh conditions en route to Europe aboard the USS Mannequin. He describes arriving in Scotland, traveling to France for further training and being sent to the front lines on Nov. 11, 1918, the same day the Armistice took effect.

His combat experience lasted only six hours, but his time in Europe extended beyond the ceasefire. Post-combat entries describe camping at Menil-La-Tour, receiving a promotion to Platoon Sergeant, recovering U.S. property from the trenches and visiting Paris.

He also candidly recounts instances of racism from fellow American troops while abroad – including being denied service at his base canteen and harassed out of a theater – and shared how his unit was assigned “background” work while white engineer units received recognition for digging trenches on the front lines.

Thanks to their granddaughter’s donation of their letters and diary to the effort, VHP can share Jessie Lockett’s and Singleton’s experiences and perspective as Black soldiers during World War I. While the program requires first-hand submissions, the stories of veterans who served long ago and have already died still may be included through similar donations of diaries or pre-recorded videos.

To read more veterans’ stories and learn more about how you or a loved one can contribute to the program, visit loc.gov/vets.

Photo courtesy of Shawn Miller (man and woman talking)

Library of Congress Veterans History Project